Open Citations - TOS

Introduction

This is the second post of a series of ten contributions about a better understanding of the different aspects of Open Science. In this post, I will outline the rationale and significance behind the Open Citation movement, to collect material for the development of a taxonomy of Open Science (TOS).

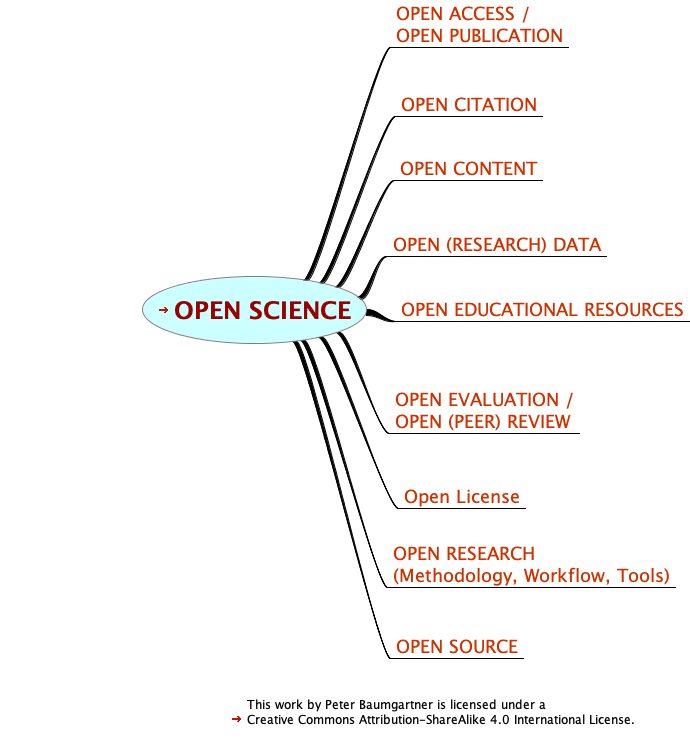

The following graphics summarizes my proposal for the first level of a taxonomy of Open Science (TOS). Branches with red pointers are active links connecting to the corresponding posts I have written so far.

**Figure 1:** The first level of a sugeested Taxonomy of Open Science (TOS)

Citations: An essential activity during the research process

In contrast to Open Access, the movement on Open Citation is not so well known. However, to build a full-fledged ecosphere for Open Science, it is essential that citations are freely available, downloadable, machine-readable, and reusable.

The following two quotes explain the significance of Open Citations:

While the act of citation by the author may be the work of a moment, the citation itself, once the citing work is published, becomes an enduring component of the academic ecosystem. Open Citation Definition

Citations are the links that knit together our scientific and cultural knowledge. They are primary data that provide both provenance and an explanation for how we know facts. They allow us to attribute and credit scientific contributions, and they enable the evaluation of research and its impacts. In sum, citations are the most important vehicle for the discovery, dissemination, and evaluation of all scholarly knowledge. I4OC: Initiative for Open Citations

Even if an article is published as Open Access, its citations are not automatically Open Citations. To qualify as Open Citations, the publisher must fulfill some conditions:

- Citations must be structured in a way that they can be accessed programmatically.

- Citations must be accessed separable from their sources, such as journals articles or books.

- Citations must not only be free accessible but also reusable.

The origins of this movement can be traced back to OpenCitaton, a project funded by JISC, a UK based organization, which provides digital solutions for the education and research. In 2016 the Initiative for Open Citation was launched, which today is the driving force behind the movement. It aims for free availability and usage of all metadata from publications with a digital object identifier (DOI) registered by Crossref. Freely available citation data are accessible through the Crossref program interface or the Open Citation Corpus. Open Citations can be used to find publications, but also for the analysis of the citation corpus as well (e.g., “how do different fields of knowledge fit together?”).

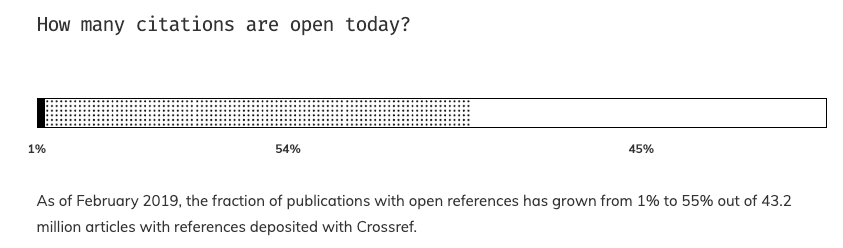

**Figure 2:** How many citations referenced by Crossref are Open Citations? (see:

Keep in mind that the figures above refer only to those citations referenced by Crossref. The relation of all scientific publication to Open Citations is much worse. The biggest problem is that Open Citations are not in the business interests of two key players: Elsevier (Scopus) and Clarivate Analytics (Web of Science).

Web of Science (WoS):

WoS (previously known as Web of Knowledge) is a commercial online citation indexing service owned by Clarivate Analytics.

Clarivate Analytics was formerly the Intellectual Property and Science division of Thomson Reuters. In 2016 Thomson Reuters struck a 3.55 billion dollar deal in which they spun it off into an independent company and sold it. Wikipedia. See more in detail the The Scientist, a magazine for life science professionals.

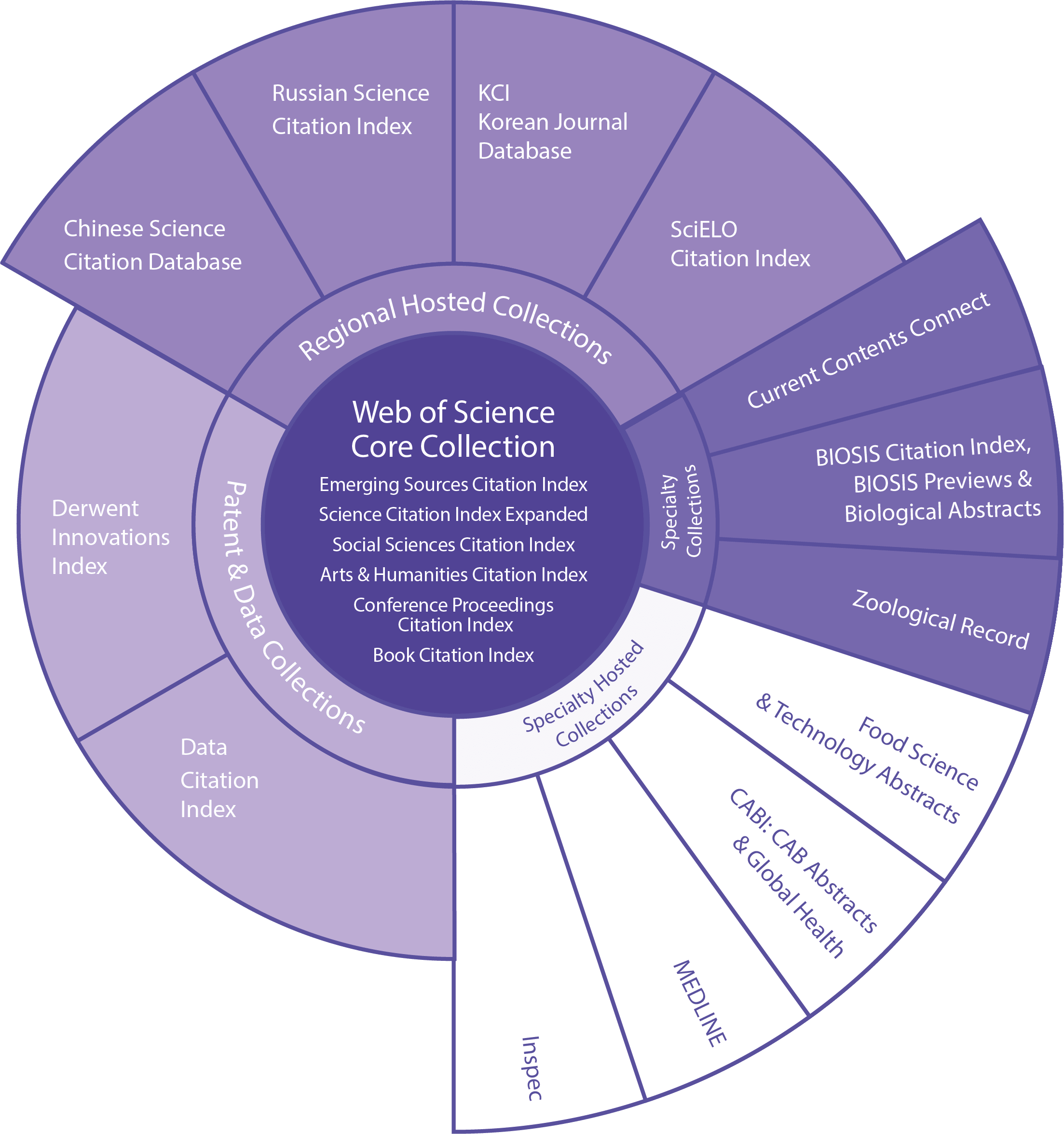

**Figure 3:** Clarivate Analytics [Web of Science product portfolio](https://clarivate.libguides.com/webofscienceplatform/introduction)

WoS is not only one product but platform with many different indexing services and several scientific literature search databases. The central product in the portfolio of Clarivate Analytics is the Web of Science Core Collection (see Figure 3). It includes:

- Science Citation Index (SCI),

- Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and

- Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI).

From the WoS Core Collection data set derives the Journal Impact Factor (JIF), published in the yearly Journal Citation Reports (JCR). Although the JIF is seriously flawed, almost all academic institution e require their researcher to play by the rules of the JIF. Only in the last few years, the critiques gather speed. So signed to date (2019-06-24) already 1,415 organizations and 14,467 individual researchers the San Francisco Declaration On Research Assessment (DORA) against the Journal Impact Factor. But not only critique but also the development of bibliometric alternatives (altmetrics) gain importance. I will cover bibliometric measures and these recent developments in other posts more in detail.

WoS has a tremendous impact on the behavior of researchers and their career development. To date (2019-06-24) Clarivate Analytics covers the following numbers of academic publictions1

| Category | WoS Core | WoS Platform |

|---|---|---|

| # of journals | > 20,900 | > 34,200 |

| # of records | > 73 million | > 155 million |

| Cited references | 1.4 billion | 1.6 billion |

To put these figures into perspectives: They cover “only” between 35% (Natural Sciences) to 12% (Arts and humanities) of all journals (> 62,500) as listed in UlrichsWeb (Ulrich’s Global Serials Directory) (Mongeon and Paul-Hus 2016),

Clarivate also possesses other vital tools and services for scholarly research:

- Endnote, a popular reference management software, formerly the property of Thomson Reuters.

- Publons: is a service for academics to honor respectively showcase their scientific work which does not lead to a “standard” publication in one of the JIF journals. The name of the enterprise is an homage to the moniker

publon, signifying the smallest publishable unit. This concept is a cynical reference to the phenomenon that for the academic career the number of publications is often more important than their individual quality, resulting in “salami slicing” of papers. - Kopernio is a technology startup, which developed a web-browser extension that simplifies the process of finding and legally downloading scholarly publications.

Clarivate Analytics acquired Publons in 2017 and Kopernio in April 2018. These purchases in recent years demonstrate that Clarivate Analytics knows how to secure its leading market position: Both services are (currently) free and are doubtless useful for the individual researcher. Besides generating revenues from publishers, Clarivate binds academics to their main product as both free services are closely related and linked to WoS.

This kind of effective use of the academic community is a well-known strategy, illustrated by two more examples.

First example:

In September 2008 Thomson Reuter – at that time still the owner of Endnote – started a lawsuit with the argument of copyright infringement for US$10 million against the developer of Zotero, the Center for History and New Media at the George Mason University’s. Back then, I wrote about this lawsuit in my German blog (Endnote klagt Zotero auf 10 Mio $ and Zotero sieht der Klage gelassen entgegen).

Thomson Reuters criticized that Zotero has reverse engineered their Endnote bibliographic citation styles where each style addresses the particular requirement of a journal. Reuter saw it as a violation of the site license agreement, especially as Zotero transformed these bibliographic styles into the XML-based open Citation Style Language.

However, the crux of the matter is that members of the community developed all these Endnote styles hosted on the Endnote website. Imagine a situation where Microsoft Word claims to be the owner of all MS Word templates, designed by us, the users! It seems that this is the way for many endeavors in academia: We scientist do the whole work free (e.g., peer review) and the commercial enterprises sell it (e.g., as quality assurance for their journals). – BTW: Thomson Reuters lost the case against Zotero (Wikipedia)

Second example:

As helpful the services of Pablons for the scientists are, we have to keep in mind, that academic work by the research community on the Clarivate website are freebies in exchange to just higher visibility of their research. Researcher track their publications, citation metrics, peer reviews, and journal editing work not only for free but it is hardly any surprise, that their writings are imported from Clarivates WoS, their Endnote bibliographic reference manager (bought with 250 US$ from Clarivate) and their citation metrics come from the Web of Science Core Collection, owned again by Clarivate.

Scopus (Elsevier)

Elsevier has even more market power than Clarivate Analytics. It owns

- Scopus, a database of abstracts and citations with a coverage from about 47% (Biomedical journals) to 18% (Arts & Humanities)

- Science Direct, a database for scientific publications and ebooks (inclusive medical journals), which sells via subscriptions

- Mendeley, a desktop and web program for bibliographic management but also a social networking website for academics with to date (2019-06-24) more than 6 million users

In contrast to WoS and Google (with Google Scholar another big player in the citation reference business): Elsevier does not only sell the usage of their database but is also the owner of a vast list of journals themselves. From the perspective of this double ownership, Elsevier’s business model is a closed circle: It includes the paid use of their database so that academics can find and cite scientific literature. The result of these citations is an increase of reputation of Elsevier’s journals through a higher Journal Impact Factor.

Elsevier is infamous for his incredibly high-profit margin, which is about 35-40%. In contrast, financial institutes and banks work with 10-15%, and the much-criticized Walmart has only about 3% profit. These figures come from the excellent and free accessible documentary “Paywall: The Business of Scholarship” (Schmitt 2018). In other posts, I will dwell more about the business model and the nasty role of Elsevier in the Open Science movement.

However, back to the Open Citations issue regarding Elsevier: It turns out that Elsevier is the biggest obstacle for a better proportion of Open Citations:

… of all 956,050,193 references from journal articles stored at Crossref, 305,956,704 (32.00%) are from journal articles published by Elsevier, none of which are in the Crossref “Open” category, freely available for others to use. Put another way, of the 470,008,522 references from journal articles stored at Crossref that are not open, 305,956,704 (65.10%) are from journals published by Elsevier (Open Citations Blog).

Summary

In this post, I have outlined the rationale and significance of the Open Citation movement. Citations reflect the structure and relationship of our scientific and cultural knowledge and deserve research in its own right. As “dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants” (Isaac Newton and nowadays also the motto of Google), we generate our knowledge from previous discoveries. Citations are the expression of a social network of interconnected links which itself are due to scientific research. Much can be learned of this interplay of different researchers, subject areas, and language communities through different times and regions.

I have also argued that the economic interests of two key players in the research business are obstacles to overcome for a higher rate of Open Citations. Clarivate Analytics form together with Elsevier a duopoly and maybe with Google even a tripoly (Schoolworkhelper 2018): Because of the competition between two or three sellers they cannot work like a monopoly and dictate without consideration their market condition. However, they can work in a kind competition-cooperation relationship; an economic framework called the coopetition paradox (Raza-Ullah, Bengtsson, and Kock 2014).

Add relevants links to the subject of Open Citation on my Wakelet page.

References

Mongeon, Philippe, and Adèle Paul-Hus. 2016. “The Journal Coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A Comparative Analysis.” Scientometrics 106 (1): 213–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5.

Raza-Ullah, Tatbeeq, Maria Bengtsson, and Sören Kock. 2014. “The Coopetition Paradox and Tension in Coopetition at Multiple Levels.” Industrial Marketing Management 43 (2): 189–98.

Schmitt, Jason. 2018. “Paywall: The Business of Scholarship (Full Movie) CC BY 4.0.” https://vimeo.com/273358286.

Schoolworkhelper, Editorial Team. 2018. “Business: Monopolies, Oligopolies, Duopoly, Tripoly.” SchoolWorkHelper. https://schoolworkhelper.net/business-monopolies-oligopolies-duopoly-tripoly/.

-

The category “journals” includes books, conference proceedings, and data sets. ↩︎

This work by Peter Baumgartner is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://notes.peter-baumgartner.net/contact.

Powered by the docdock theme for Hugo.

Privacy | Disclaimer